Guide For Teachers

IN MY POCKET PROJECT FOR SCHOOLS

GUIDE FOR TEACHERS, EDUCATORS AND FACILITATORS

The WE ARE HERE! Foundation, based in Perth, WA, is a not-for-profit organisation. In our education programs, we show young people that each person can make a difference, regardless of their personal circumstances. By sharing the stories of Upstanders, we inspire young people to be confident, so they can stand up for what’s right in the face of prejudice, discrimination, and oppression. We empower them to create the change they want to see in their communities and the world.

Eli and Jill Rabinowitz

+61 414 375111

OUTLINE

- Historical Background

- Source Material

- In My Pocket Overview

- Project Significance

- Goals and Outcomes

- Step by step Guidelines

- Conclusion and Evaluation of Story Component

- Reflections

- Create Your Own Pocket

- Conclusion and Evaluation of Art Component

We begin with background Information, followed by the guidelines for how to run the workshop, from introducing the book and reading the story, to the guided process of thinking about, discussing, and answering questions. We will provide a video of the story and a PowerPoint presentation for showing the students, and further information for the teacher. This culminates in the art and craft activity inspired by the themes of the story.

Historical Background

Kristallnacht

On 9-10 November 1938, Nazi leaders unleashed a series of pogroms against the Jewish population in Germany and recently incorporated territories. This event came to be called Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass) because of the shattered glass that littered the streets after the vandalism and destruction of Jewish-owned businesses, synagogues, schools and institutions, books and possessions, and homes.

Many thousands of Jewish men were incarcerated and killed. This was the start of arrests made simply on the basis of ethnicity: being Jewish.

The Kindertransport (German for “children’s transport”) was an organised rescue effort of unaccompanied children (but not their parents) from Nazi-controlled territory that took place during the nine months prior to the outbreak of World War 11 in 1939. Jewish organisations within the Greater German Reich planned the transports. The United Kingdom took in predominantly Jewish children from Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia and Poland. The children were placed in British foster homes, hostels, schools, and farms. Often they were the only members of their families who survived the Holocaust. The program, organised by British child welfare and philanthropical organisations, was supported, publicised, and encouraged by the British government who put no number limit on these child refugees – it was the start of the War that brought it to an end, at which time about 10,000 Kindertransport children had been rescued and brought to the United Kingdom, including around 800 to Scotland.

In Dorrith’s case, it was the impact of Kristallnacht in November 1938 that decided her fate. The Night of Broken Glass reached Kassel, Germany where the Oppenheim family lived. This shocking pogrom, along with all the other persecution experiences, repressions and restrictions imposed by the Nazis on the Jews, resulted in her parents sending her on a Kindertransport to the safety of the UK.

Kristallnacht https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/kristallnacht

Dorrith’s own words to describe Kristallnacht in her streets. “I can still picture that farewell.” https://elirab.au

Kindertransport https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/kindertransport-1938-40

Documentary (Kindertransport) – Into the Arms of Strangers

Dorrith Sim Biographies and Interviews on website https://elirab.au

Source Material

Ms Julia Drinnenberg is an art teacher and librarian, from Hofgeismar, a town in Germany not far from Kassel where Dorrith Sim had lived. She runs a two-day workshop for 9-12 year olds who come to the Stadtmuseum’s studio where they read and discuss In My Pocket, do activities related to the story and Dorrith’s life and times, and create art and craft pieces inspired by their own reactions to the story. The WE ARE HERE! Foundation acknowledges Ms Drinnenberg’s contribution to and support of their In My Pocket project in Australia.

Scotland – Scottish Jewish Archives, Glasgow; University of Glasgow; Gathering the Voices, Glasgow; University of Edinburgh; Dorrith Sim’s children and grandchildren https://elirab.au

In My Pocket Overview

The autobiographical picture book In My Pocket by Dorrith Sim tells how, as a 7-year-old Jewish girl, Dorrith Oppenheim had to flee Germany, all alone, to live with an unknown family in Scotland until the war ended. The separation from her parents would be final. Dorrith’s story is sad, yet first and foremost it is the story of her rescue, her resilience and coming to terms with her new and happy life.

The book describes from a child’s viewpoint and vocabulary what it was like on the train to Holland and the boat to England. Small kindnesses along the way, the generosity of her foster family and acceptance by her new Scottish friends, loom large against the backdrop of war.

The poignant yet powerful impressionist-style illustrations and sepia prints of Dorrith’s photo, visa and identity certificate add a sense of reality and are reminders of the refugee experience. She knows no English: all she can say is “I have a handkerchief in my pocket”, and when she learns a new word, she puts it in the same sentence: “I have a dog/teacher in my pocket”.

Can such stories be read to young children without overwhelming them? Would such a story resonate with them?

The author herself answered this question with a ‘yes’. It was important for her to tell children what happened to her as a little girl. She wanted children to learn what it means when people are excluded, when they are shunned or persecuted because of their religion, or their heritage, or their nationality, or the colour of their skin. She felt that children should be able to put themselves in the shoes of those affected and become aware of discrimination in their own everyday lives.

Dorrith Sim lets the children’s book end with the moment when her parents’ last letter to the child arrives in Scotland – it remains unclear why no further letters followed.

What happened to the parents? This question inevitably comes up. How does this project deal with that?

The open ending of the book suggests that Dorrith Sim doesn’t want to burden children with the fact that her parents were murdered, regardless of their emotional resilience. Parents, teachers and educators who use this book should decide, depending on the developmental stage of the children, whether they avoid the fact of their cruel death in Auschwitz – which is unbearable even for adults – and accept that her parents died during the war.

The appropriate age range for this book is from 9 to 12 years, although it must be taken into consideration that some children are already informed about Auschwitz.

As in the book itself, the War and the Holocaust are not left out within the project, but in their incomprehensible dimensions they are not made the main topics. The focus is on rescuing the children and coping with a new life despite their traumatic experiences.

Dealing with the persecution experiences of children in Germany during the Nazi era and their escape from National Socialist Germany gives younger children of primary school age access to the history of the era without overtaxing them.

At the same time, In My Pocket’s themes enable a new perspective which can bring relevant discussion to a contemporary reading of the book.

Project Significance

Today, there are millions of refugees and displaced people, many of whom are children. This project highlights their difficulties when leaving their country of origin and settling in a new country. They would experience language, identity and belonging issues, the changing of family roles and cultural differences. As an example, there are currently two million refugees from the Ukraine in Poland alone.

From the historical perspective of the In My Pocketproject, its message is as relevant as ever before: the project originates from an important period in history, the Kindertransport (1938-39), when 10,000 children were forced to leave Germany and other Nazi occupied countries (without their parents) and relocate to the United Kingdom. The Kindertransport experience is relevant as it reflects the global movement of people today.

In My Pocket by Dorrith M Sim is an autobiographical picture book. The story is told from the perspective of a young person, and educators acknowledge that lived experiences of others have universal appeal. This project translates across all communities. It provides a clear link to what young people from diverse backgrounds could see and face about their own and others’ ethnicities.

Being a story of rescue, survival and hope for the future, the story also embodies the principle of staying connected to one’s heritage, and suggests that refugees are resilient and can thrive in their new environments.

Goals

● To introduce positive, effective, and long-lasting changes in children’s attitudes and behaviour.

● To be aware of exclusions based on religion, heritage, race, gender, social and economic status, academic ability, physical appearance and disabilities.

● To show empathy and compassion for others who may be living in extraordinary circumstances.

● To be inclusive, be welcoming and offer a sense of belonging; show kindness. Be non-judgemental: show respect and tolerance.

These are important themes in the In My Pocket story.

Outcomes

* A greater understanding of what it means to young people to stand up for what is right in the face of prejudice, discrimination, and oppression.

* Empowerment of young people to create the change they want to see in their communities.

* Engagement in learning and dialogue that encourages young people to become intellectually and emotionally comfortable with difference.

In My Pocket Step by Step Guidelines

Overview

The program is aimed at children (students) aged 9 -11 years.

The program is in the form of a two-hour workshop attended by up to 32 students, depending on the size of the Year 5 or 6 class/es.

In the following, the In My Pocket project is outlined in individual work steps.

Should the teacher wish to focus on the historical background in more detail, more time would be required.

PowerPoint

The book is on the PowerPoint and should be on the screen so that the students can follow the story, page by page.

Workshop

The 2-hour workshop with suggested time for each step:

At the discretion of the teacher – background information about Dorrith Sim’s life and times. This could add on extra time to the workshop.

30 minutes: Teacher will introduce In My Pocket and then read it aloud to the students. Don’t give them the mini books yet.

The book is on the screen for the students to follow the story, page by page.

During and after the reading, the teacher will engage in questions, answers and discussions.

10 minutes: The students will watch a video and a PowerPoint.

5 -10 minutes: Teacher will explain the art & craft activity – painting calico pockets.

Students will be seated to receive their own free mini copy of In My Pocket.

Each student has at their place setting a calico pocket and art equipment.

70-75 minutes: Teacher will guide the students in the painting of the pockets.

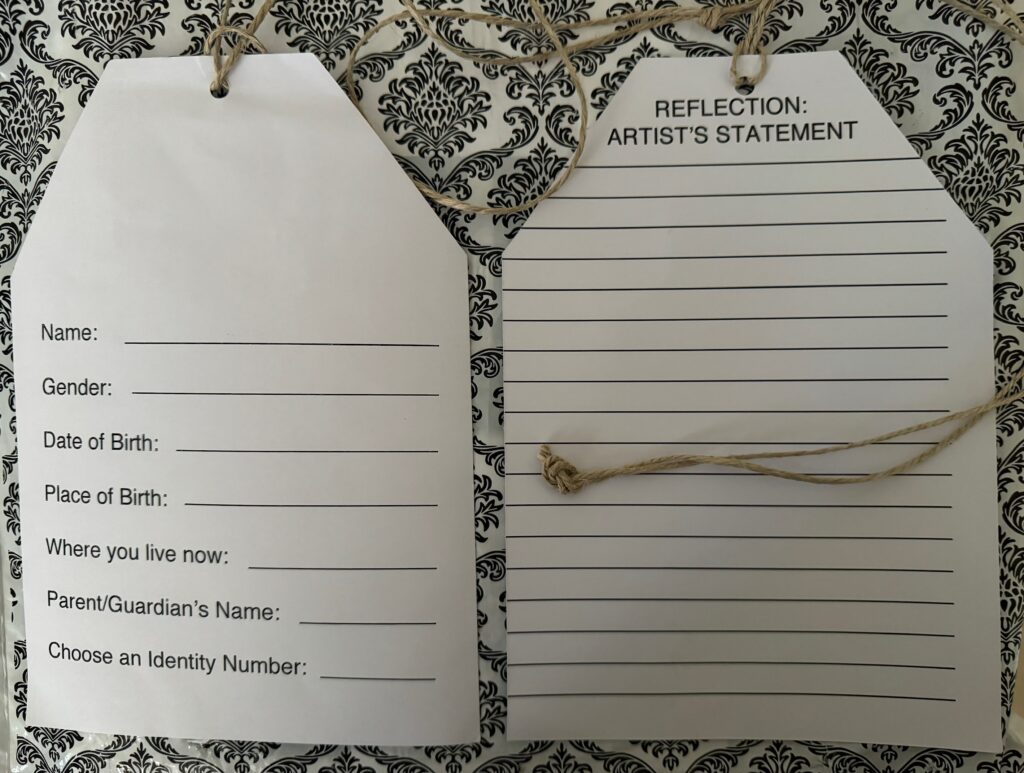

While the pockets are drying, Teacher will give the students the identity cards (name tags, labels) to complete.

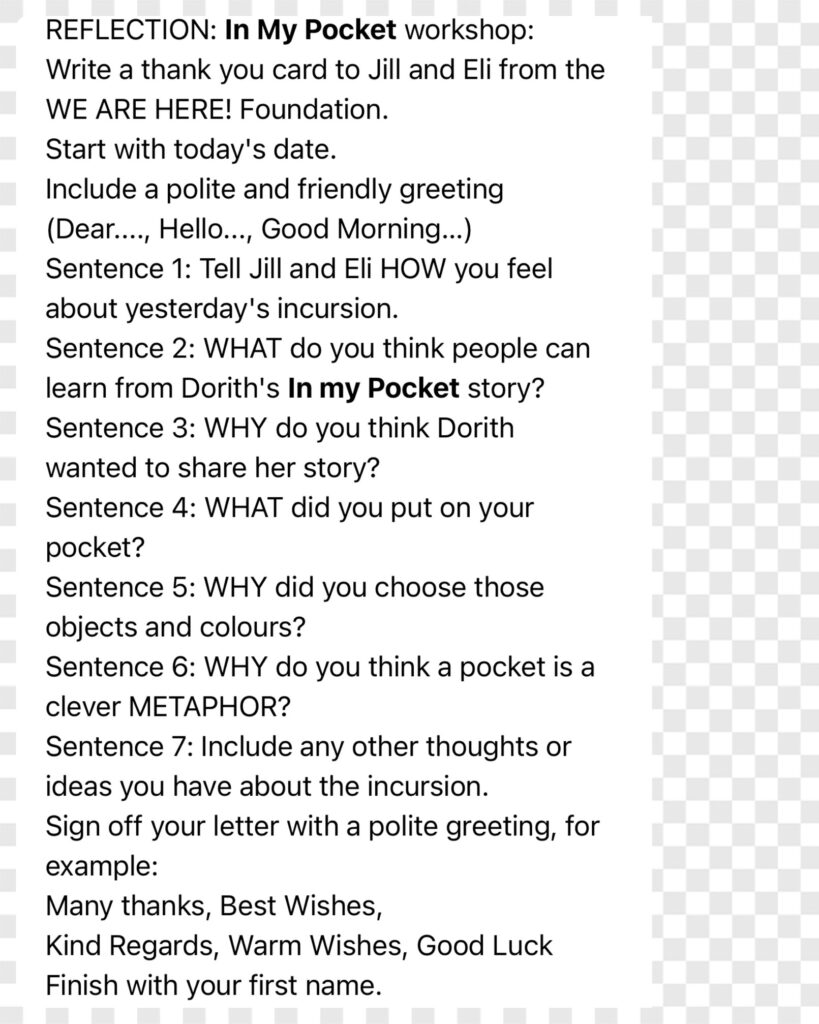

On the back is the Reflection: Artist Statement. This can be completed later.

Teacher will invite the students to share their pockets: written or oral reflections on how the story resonated with them; on what they painted and why.

Each student receives a Certificate of Participation.

Each student takes home, in their own decorated calico pocket, the mini book, the identity card and the certificate.

Introduction

T = Teacher; * = Question asked or T’s comment

T: *Today you will hear a story. It happened eighty-five years ago, just before WW11 began. It is a true story of children your age and even younger who had to flee from their homeland, Germany, all alone, without their parents. They had to escape because they were in great danger. They were Jewish and Jews were being persecuted by the Nazi government of Germany which had introduced racist laws and removed individual rights and freedoms. People in Britain (England) and Scotland organised a big rescue operation for these children, but not their parents, and one of those children was Dorrith Sim, who wrote this story about her rescue.

T: Look at cover of book * What do you think this cover is showing us about the story to follow? Students will give suggestions.

T: * What do we call a story written by you about your own life? Autobiography

T: Read blurb * What historical facts does this blurb give us? Students will give suggestions.

T: Study the documents * Why are they included and what purpose do they serve? Sepia – old, real, authentic; poignant reminder of the story’s origins in history; some refugees today also have these types of documents.

Read Page 1 (Hardly anyone…)

T: * Do you think children are on the run from danger today? Can introduce the themes of refugees, displaced people, and the issues raised above in Project Significance.

(In the PowerPoint there is a photo comparison exercise of two refugee girls, 1939 and today – * Describe these two pictures, compare them, what is different in each case, what is similar? What does the comparison of these two pictures tell you? The students should, on their own initiative, draw parallels to today’s flight experiences of their peers traveling alone who come to us from war zones. Ukraine girl. Also, from dangerous places like Central America where unaccompanied children are fleeing to the US border. Can ask where Australia’s refugees come from.)

T: Story is written in first person plural (we). * Why? Collective experience: the children get support and comfort from each other as they are all experiencing the same thing; there are no individuals here.

T: * What do you think Dorrith could be thinking about as she gazes out from the deck? Is she looking back or forwards? What could the white seagull represent? Freedom – link to the word “danger”.

Red ribbon and toy dog motifs. A motif is a recurring element in a story that points towards the theme. An object that represents an idea, in this case the theme or idea would be love. Red is the colour of love. Notice how the red ribbon weaves its way through all the illustrations, first lovingly put in her hair by Mummy and Daddy, and at the end she is still wearing it, thus connecting them and her past to her new parents, new life. Toy dog motif and real dog connect the past and present.

Read Page 2

* What did it mean for the parents to send their young daughter so far away? Students will give their own suggestions.

* Dorrith had to travel to England all alone without her parents when she was 7 years old. What did she think when saying goodbye to her parents on the Hamburg Station? Imposing close up of the train, dark and menacing, like the atmosphere on the station. Loss and pain of farewell represented by the browns. Students will give their own suggestions.

* How would you feel if you were in her place? Show compassion.

Connecting the students with a real, lived experience can show their empathy.

Read Page 3

T: * Who is the child who has dropped her toy dog? Why is this written in third person POV?

T: Switch from first person plural to third person point of view * Why? Perhaps not ready yet to focus on herself.

*Have you ever travelled alone, without your parents? Did you bring your stuffed animal with you?

*Have you got or did you have a cuddly toy and what meaning does/did it have for you?

*What did it mean to Dorrith?

Her toy dog is called Droll. Students can tell each other about their stuffed animals. Why ask this? A stuffed animal or favourite toy is a way to bring comfort and help children feel safe and secure, calm, and soothe fears, especially in the dark and in unknown places and when separated.

T: * What are the children wearing around their necks and why? Identity documents, and numbers.

Children all together, confined, in the carriage, comfort each other.

T: * What do you think of the man who rescues her toy dog and throws it back to her? Kindness of strangers. Can explain the bigger picture here as the man could be a metaphor for the rescue operation itself, the Kindertransport. Wave goodbye to her past life.

Read Page 4

T: * What are the clues in the illustrations that show us where the children are having their picnic, and what is Holland called now? Open fields, tulips, windmill; the Netherlands

T: * How are the children feeling and how do we know this? They had been confirmed to the train carriages. Bright cheerful colours especially yellow which is associated with optimism, friendship and happiness. Sunny weather, children relaxed and smiling, eating and enjoying treats like chocolate, milk and cheese; food would have been scarce; feeling of freedom; Dorrith has put down her toy dog showing she feels safe. They are confident enough to sing aloud as perhaps they’d had to be quiet before, subdued or afraid. Note the kindness of strangers again here (Dutch gave food). Contrast to what these children had been experiencing – persecution, deprivations. Mermaids are from a fantasy world so this could suggest they feel this situation of freedom is almost unreal.

Read Page 5

T: The children are wearing pyjamas, trying to do normal, ordinary things. * How would you feel if you had to travel so far away, without your parents? Do you sympathise? Most children have these fears about sleeping alone and would be disorientated. Dorrith is an only child and is alone, so this is a poignant reminder of her status. The phrase “could not remember the way back” could suggest there was no going back to their former lives. This is called foreshadowing.

Read Page 6

T: Build up of tension. Change to first person (I) point of view and we finally have Dorrith’s own voice. * What does this tell us about Dorrith herself, at this point? * Why did Dorrith cry so much when she got off the ship in England stepping over the jetty to land? She feels afraid. She has finally accepted the reality of her situation and that she is on her own; this is the start of her new life as an individual; she is alone. Before, she was part of a group that was doing everything together. She is no longer part of the security of the group. Note red ribbon and toy dog and ID tag which are her identity. Note what Dorrith is carrying – the suitcase. * What do you think is in the suitcase? Practical items for the future and sentimental items from home. Memories are attached to objects reinforces the first mention of a place to store things, a repository, leading to the pocket idea later on in the story. Note the illustrations, blurry depiction of Dorrith showing her fear.

Read Page 7

T: * What are the adults doing and what are the children doing? Where is Dorrith? Again, we see kindness of people prepared to take these children into their homes. Images show the adults with outstretched arms, welcoming them. People are on left in a tight group, showing solidarity. Children are separated, showing them as individuals. Dorrith on right, waiting and watching. Note elegance of architecture of the station, light and airy with the beams and arches reaching upwards, suggesting hope and permanence. (Liverpool Street Station – see pictures on PowerPoint.) Compare with the Hamburg station (dark colours, huge imposing train in foreground, dirty and grimy).

T: * Who are the men with cameras and why are they taking photos? Newspaper photographers. Need to publicise the rescue operations (Kindertransport) to get more people to take in children, get more donations and volunteers to fund the operation.

T: * How do we know that the children coming to live in England wasn’t meant to be permanent? See last paragraph which alludes to the UK conditions of the Kindertransport.

Read Page 8

T: * How can we tell that Dorrith has been specially chosen? “That’s how they found me” shows us that she has a distinct and separate identity, reinforced by the red ribbon and the toy dog. Links to what her parents had dressed her in.

T: *Look at the people’s clothes and demeanour; why is the man kneeling? They are wearing smart clothes, are well-off, smiling, welcoming and have a good relationship with each other; man kneels to eye level to connect with Dorrith, make her feel safe and special. Gallimore family.

Read Page 9

T: Man speaks German to Dorrith. First words he says are Welcome, lovely child. Complimenting her. A real dog. Man’s comforting and protective hand on her shoulder. * Why these details? To put her at ease, she will understand the German, showing kindness. Dorrith still looks wary, especially of the dog. * What kind of dog? Westie – terrier name: Rogie

T: * Here begins the learning of the English language. * Do you think this is a good way to learn English? Students can share with each other what they would put in a pocket.

T: * Here’s our first reference to the pocket: what do you think it represents? Taking ownership of something, keeping it safe and secure, just like Dorrith feels now, with the Gallimore family. Pocket now becomes a symbol of her new life through the new words and customs.

Read Page 10

T: Compare life in Scotland with Germany. * What differences does Dorrith discover? Modern and affluent, no deprivations. Vati probably wasn’t permitted to own a car and no pets were allowed. Looking forward, not back. Car (Austin 7) and real dog (name: Rogie) are luxuries to her.

Old world in the foreground, looms large as if she’s looking back one last time at her life with Vati; new world in the background that she will turn to and look forward. Car.

T: * What is different about Dorrith in this picture? Not wearing a number or carrying her toy dog, showing she has been claimed and feels safe.

Read Page 11

T: This is the climax of the story. First time she identifies as being Jewish. * This is the only time Dorrith reveals openly that she is Jewish. Why? She feels safe enough to do so; she is accepted by her new friends who don’t care that she is Jewish, not discriminating; she knows she won’t be ostracised by them or shunned because of a Nazi imposed persecution law. She knows and accepts she is Jewish and doesn’t try to hide it or feel scared or ashamed.

T: * What do you think; how would you react if you experienced something like that in your class or social group? Students will give their own suggestions.

T: * Do you know any migrant or refugee children, or children who had to flee foreign countries because of war or religious persecution? We live in a multicultural, diverse community here in Australia.

T: * What would you do if you notice children being excluded for whatever reason? How would you make them feel welcome?

T: * Do you realise that they would have to learn a new language, new customs, make new friends? Just like Dorrith.

T: * Do you think they should be encouraged to always remember their heritage?

T: Parents’ names. Show different status. * Why are her two sets of parents called these names? Her Scottish parents are Mummy and Daddy as she accepts them as such, but she hasn’t been prevented from remembering she has real parents in Germany. Acknowledge her heritage.

T: * What do you think of the Scottish foster parents taking in Dorrith? Students will give their own suggestions, focussing on their kindness and compassion and wanting her to feel like she is their daughter by calling them Mummy and Daddy.

T: * What clues do we get from the illustration about how Dorrith feels? Happy, lighthearted, having fun, holding hands all show that she has been accepted by her new Scottish friends. Summer clothes also add a touch of a carefree open life.

Read Page 12 (last page)

T: * Why would mushroom picking be significant? Dorrith and her parents, the family, did this together so reminding her that she is missed and that she mustn’t forget them; mushroom picking was a popular pastime in Germany; Dorrith hasn’t forgotten this tradition and still hopes to see her real parents soon;

T: Two important ideas here – open-ended conclusion to the story and the pocket theme. The students will ask what happened to her parents, and what happened to Dorrith.

T: The book ends quite suddenly. Dorrith receives a last letter from her parents although she doesn’t know this at the time. Responses should be sensitive to the student group. The open ending suggests that Dorrith doesn’t want to burden children with the fact that her parents were murdered in Auschwitz.

T: * What do you think her parents wished for their child when sending her to Scotland? Students will give their own suggestions

* Could Dorrith fulfil their wish for her to live a happy life? Students will give their own suggestions and Teacher can give a brief biography. Rescue, hope and resettlement. Refugees can thrive. Don’t need to lose connection to one’s heritage.

T: * Why do you think Dorrith wrote this particular story aimed at children? She wanted children and others to know what happened to her as a little girl, and what she and fellow Kindertransport children experienced. She wanted them to be aware of what discrimination and persecution means (in all its forms) and be able to put themselves in the shoes of those affected.

T: Brainstorm what the pocket could symbolise in relation to the theme/s of the story. Refer to students’ answers later when the calico pocket is shown. Some suggestions could be literal, such as things she pretended to put in her pocket to help her learn English. Others might identify a deeper meaning of what the pocket represents in Dorrith’s life, eg, the pocket is a symbol of putting away her old life and looking forward to a new life; an enclosed space for remembering the precious times and items of the past; things and memories are kept safe in a pocket.

T: * What is the significance the red ribbon motif? It connects her old life to her new life by entwining the love of her real parents to the bonds created by her new parents. The theme of kindness is reflected in the weaving of the red ribbon through the story.

The real dog has replaced the toy one which could show she has survived and can live a safe and secure, happy life.

Conclusion and Evaluation of Story Component

T:* Can you find examples of people showing kindness and acceptance towards Dorrith and her fellow Kindertransport? Station man picking up her toy dog and giving it to her (rescue theme); Dutch people giving them food; Friends, family and foster parents meeting them with arms outstretched in welcome at the station in London; Dorrith’s foster family recognising her and welcoming her in German to make her feel at ease; acceptance by the new Scottish friends; being able to call the foster parents Mummy and Daddy showing they regard her as their daughter. Dorrith’s own parents Mutti and Vati have demonstrated enormous kindness by sending her away to a safe place.The big picture is the Kindertransport rescue operation itself.

T: * What did you learn for your own life? Students will give their own suggestions.

Some of the below may have already been discussed with the students.

T: * Do you know any refugee children or children who have had to flee foreign countries? Do you know why they had to leave? Teacher will monitor responses.

T: * If you noticed children being excluded, what would you do to make them feel welcome and comfortable? How could you help them? Would you ignore their differences? Would you protect them from other children bullying them by standing up for them? See Project Significance.

*** Why would the Teacher ask these questions? Refer to Goals and Outcomes.

● Brings relevant discussion to a contemporary reading of the story.

● Opportunities to suggest parallels with personal experiences of children the students interact with at school and elsewhere.

● The experiences of migrants in our multicultural communities could be revealed.

● Awareness of global movement of people and how this impacts society.

[Teacher information: Cross Curricular Links to Themes]

Reflections

Show Video – Points of Arrival https://elirab.au/points-of-arrival/ T: * What did you think of it, the way it was made in a modern setting and with a young girl?

Show PowerPoint

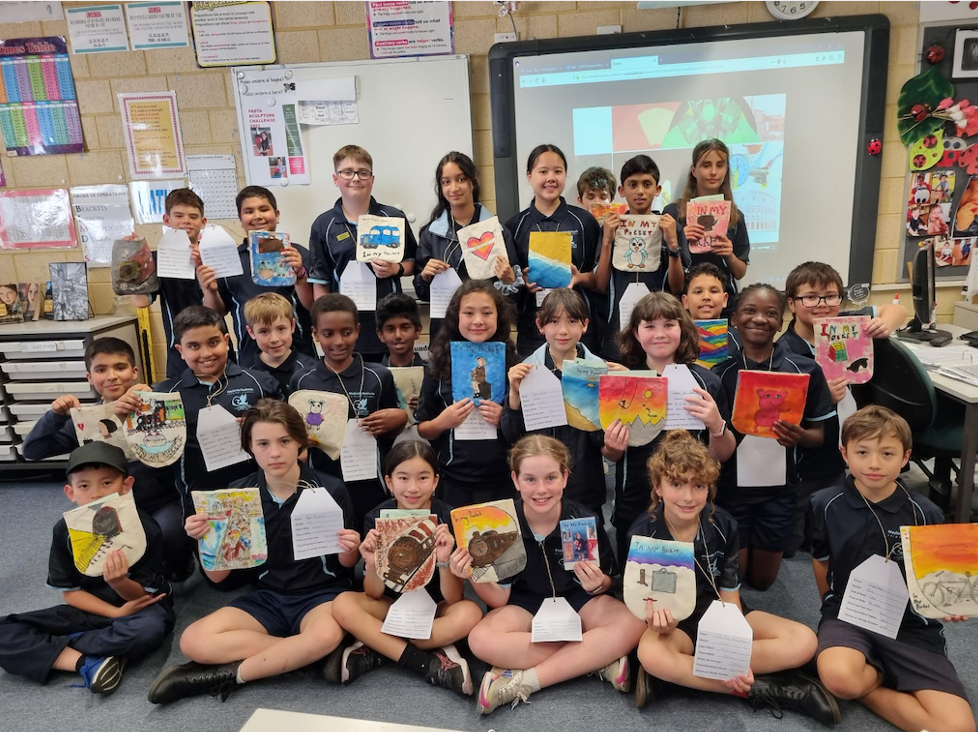

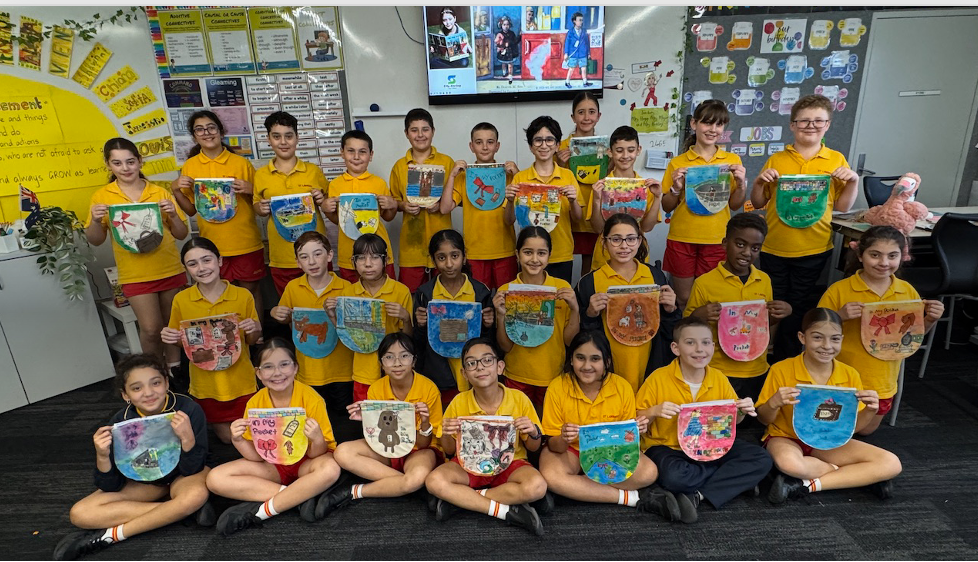

In My Pocket Project Videos Of Presentations

Example – Year 5/6 – South Perth PS – 20 October 2025

Example – Year 5 – Caversham Valley PS – 6 September 2024

Example – Year 6 – Victoria Park PS – March 2024

Example – Year 6 – West Balcatta PS – May 2024

Teacher can comment on each slide.

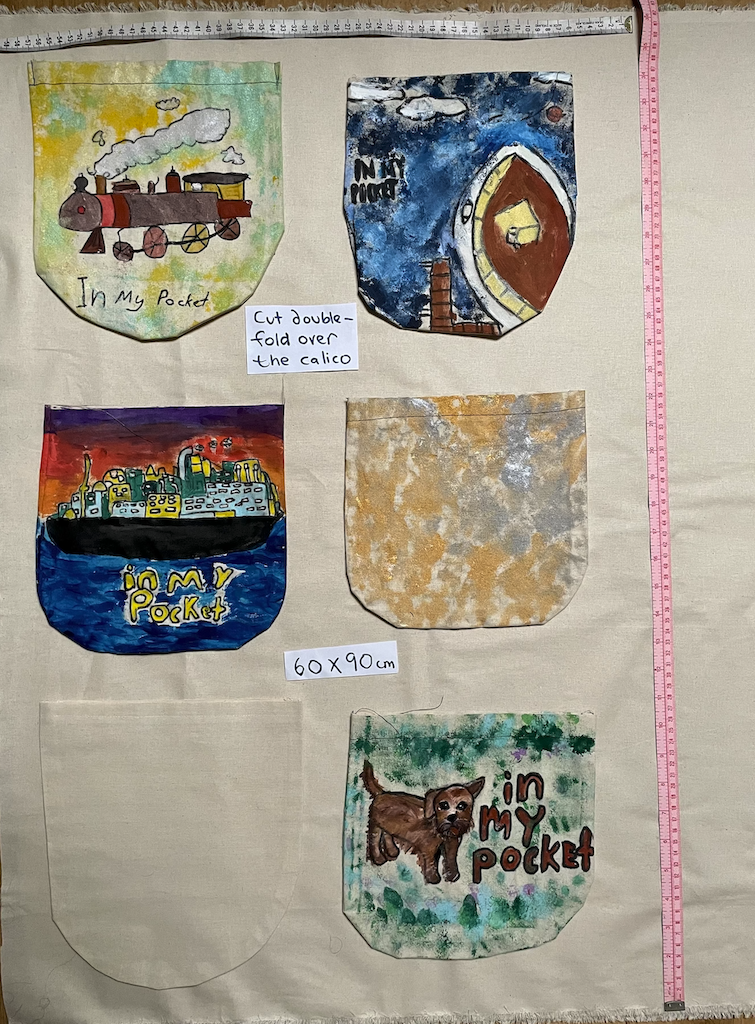

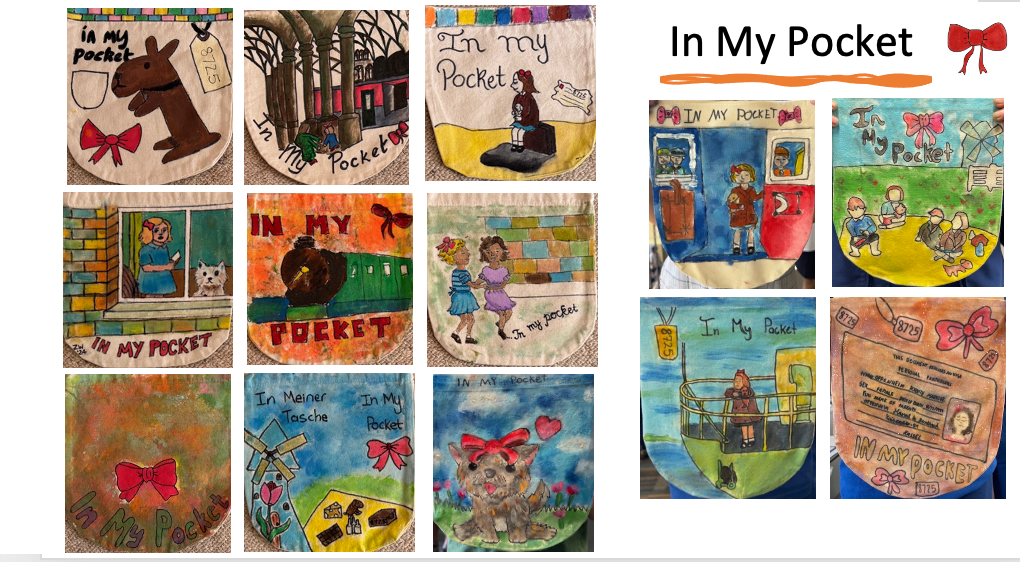

T: The last slides in the PowerPoint shows some of the calico pockets that students and others have made.

Notes for the IN MY POCKET PowerPoint:

** Mini In My Pocket books should not be distributed yet.

Slides 1 – 4: In My Pocket story – read and discuss

Slide 5: Map of the world to show context

Slide 6: Map of Europe in 1939

Slides 7 – 18: In My Pocket story – read and discuss

Slide 19: Video of In My Pocket. This is a contemporary video with commentary of the context, photos of Dorrith and her family, and excerpts from the book (images and text).

Slide 20: Three images of Dorrith – a girl, a young woman and an older lady.

Slide 21: Dorrith as a baby with her parents Gertrude and Hans Oppenheim (Mutti and Vati) in Kassel, a city in Germany.

Slide 22: Dorrith in her classroom in Germany, before Jewish children were no longer allowed to attend school.

Slide 23: Two little girls wearing their numbers. This shows how young some of the children were who went on the Kindertransport.

Dorrith’s granddaughter Eilith posed for the launch of the book In My Pocket.

Slide 24: ID documents, visa, passport, etc so that Dorrith could leave Germany and enter the UK. Note Dorrith’s number – 8725. Note sepia colours, showing they are authentic historical documents. Show the ID Cards – activity to help the students make the connection to the labels the Kindertransportees wore to identify themselves.

Slide 25: Dorrith’s actual suitcase is held in the Scottish Jewish Archives in Glasgow. She brought with some cutlery with her name engraved on the pieces. It was a common practice to give engraved cutlery as gifts to new borns. This is her ski cap and dressing gown. Refer back to what the students suggested was in her suitcase, both practical and sentimental or treasured items.

Slide 26: A selection of photos of Dorrith with her red bow, her identity. She’s holding the toy dog, Droll. Eli colourised the photos which were originally in black & white.

Slide 27: Juxtaposition of two refugee girls from different eras, 85 years apart, to make comparisons. A girl from 1938/9 and a girl from last year, from Ukraine.

Slide 28: Trace Dorrith’s and the Kindertransport journey. How long did it take? Ask for suggestions. It took a few days as Europe is not a very big area and the transports had to move fast.

Slide 29: The ship (boat), the Vienna, went back and forth across the English Channel from Rotterdam to Harwich. It was big so no wonder children got lost. An example of a ticket.

Slide 30: Famous photos of Kindertransport children arriving at stations across London. These photos and others like it were printed in newspapers all over the world to publicise the Kindertransport rescue mission. Money and volunteers were needed, as well as to show its altruistic intentions.

Slide 31: Liverpool Street Station, London, now, photo taken by Eli who was there last year. Compare to Hamburg train station on page 8 (see the lesson plan).

Slide 32: Liverpool Street Station, London, now, to show how accurately the artist captured the soaring pillars and beams and the light streaming in, giving hope for a bright future. See page 13.

Slide 33: Video – King Charles at the Bundestag (Parliament) in Germany, making an important speech about the Kindertransport. This shows the significance and impact of the rescue operation.

Slide 34: King Charles at the Hamburg memorial statue, and the statue at Liverpool Street Station. Note the violin case – children could bring what they could carry.

Slide 35: Other Kindertransport statues in cities around Europe and England. Most of these statues are the work of Frank Meisler.

Slide 36: Paddington Bear: the theme of compassion for the displaced was present in the Paddington stories from the start. Michael Bond spoke often of how the character was inspired by the sight of Kinderstransport refugee children and evacuees to the countryside arriving at train stations around London when he was a child during the War.

These children wore labels around their necks and carried small suitcases containing treasured possessions.

Paddington is all about the power of embracing people who are different. His character embodies kindness, especially towards strangers, tolerance, politeness and respect.

The stories can be interpreted as a metaphor for a humane and welcoming refugee policy. The bear could represent immigrants as being kind, sincere, diligent and warm hearted. His persevering nature suggests that if we work hard and never give up, we will succeed. He sees the best in humanity, reminding us that love and kindness can triumph.

Slide 37: The model of car, an Austin 7, owned by the family who Dorrith went to live with in Edinburgh, Scotland. This is the car featured on page 16.

Slide 38: Fred and Sophie Gallimore, the couple who warded Dorrith, had no children when she arrived, and went on to have two daughters later. The photo is of Dorrith with four of her five daughters. She also had a son.

Slide 39: Dorrith and Andrew Sim as a young couple. Dorrith and Andrew when they went back to Kassel, Germany to see her birthplace.

Family photo – ONE child, Dorrith, was saved and this is her legacy, her descendants, her family. She had passed away already, in 2012.

Slide 40: Video – a short excerpt from an interview with Dorrith in 2011, giving her message to children today.

Slide 41: How Dorrith learnt English – putting words in a “pocket”, a metaphor for a pocket in her brain/mind/memory.

CREATING POCKETS:

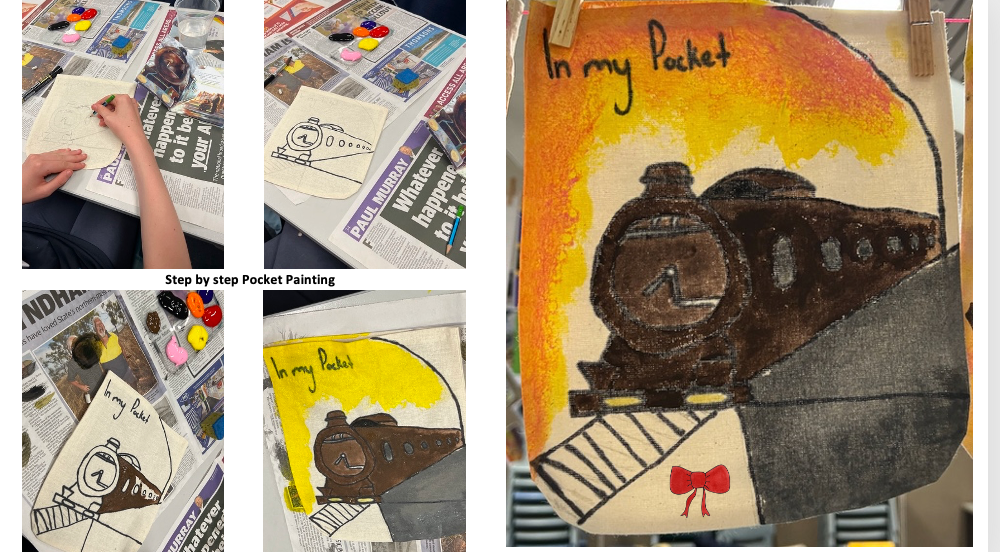

The pocket painting should take about 1 – 1 ½ hours. This may include time for the ID cards and Reflections.

Take photos of individual pockets and class photos. Please share with us!

At this point, distribute the mini books, In My Pocket.

Slide 42: Examples of pockets, especially how to write In My Pocket which must appear on the pocket (bold black marker, bubble writing, etc), and how to use the sponge and paint.

Slide 43: Lots of pockets to show what can be painted on them. Pick out examples. All must be connected to the story in some way, eg. a scene from a page can be copied; a motif (red bow, toy dog, ID label); an image (real dog, train, boat, picnic, letter, bicycle, ID documents, tulips, windmill); interpretation of any aspect of the story or the images on the PowerPoint (the wall, cutlery, map, car, pocket).

OR the teacher can discuss with the students what they would put “in” a pocket, metaphorically. The pocket is a symbol of where and how we store precious memories, items, ideas, objects, etc. The students could select six (or any number) images that represent what is important to them, and then paint them, including abstract ideas, eg their ethnicity or religion, a footy ball, a ballet tutu, a book, a pet, a computer, their school, friendship, love, parents, the weather! There must also be an image represented that’s a nod to the story, eg the red bow is the most significant.

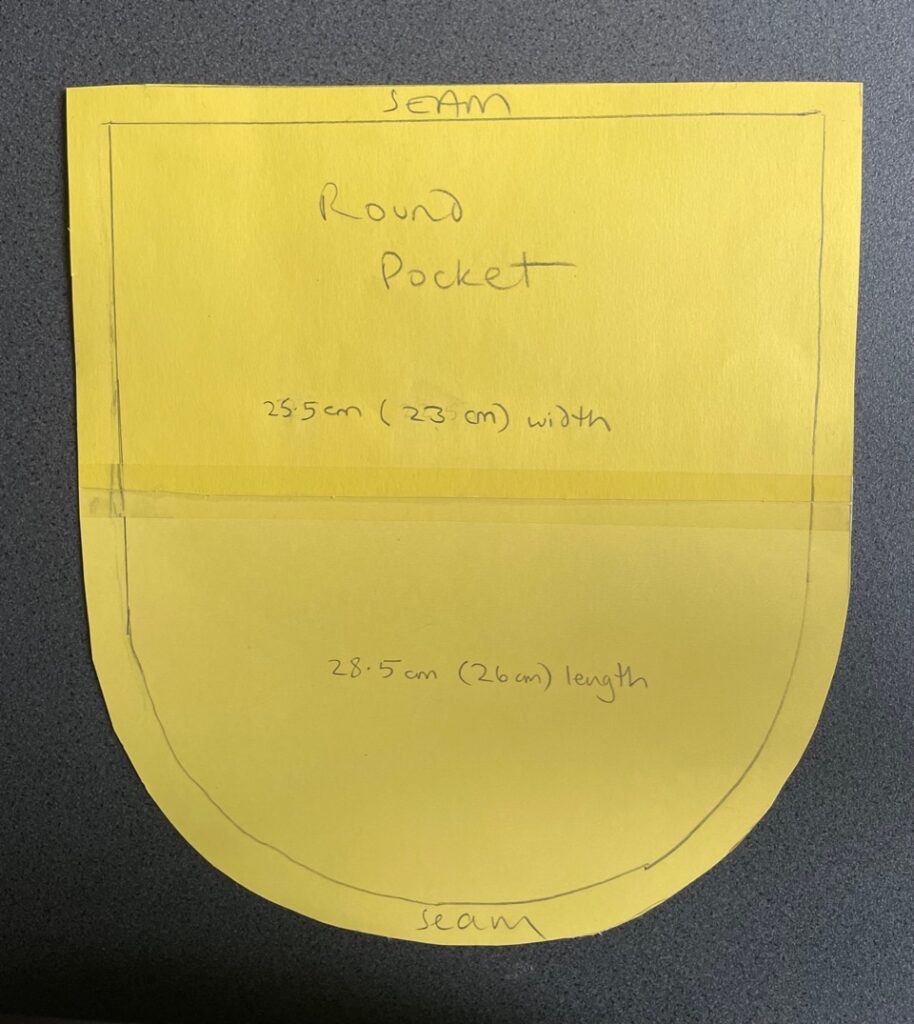

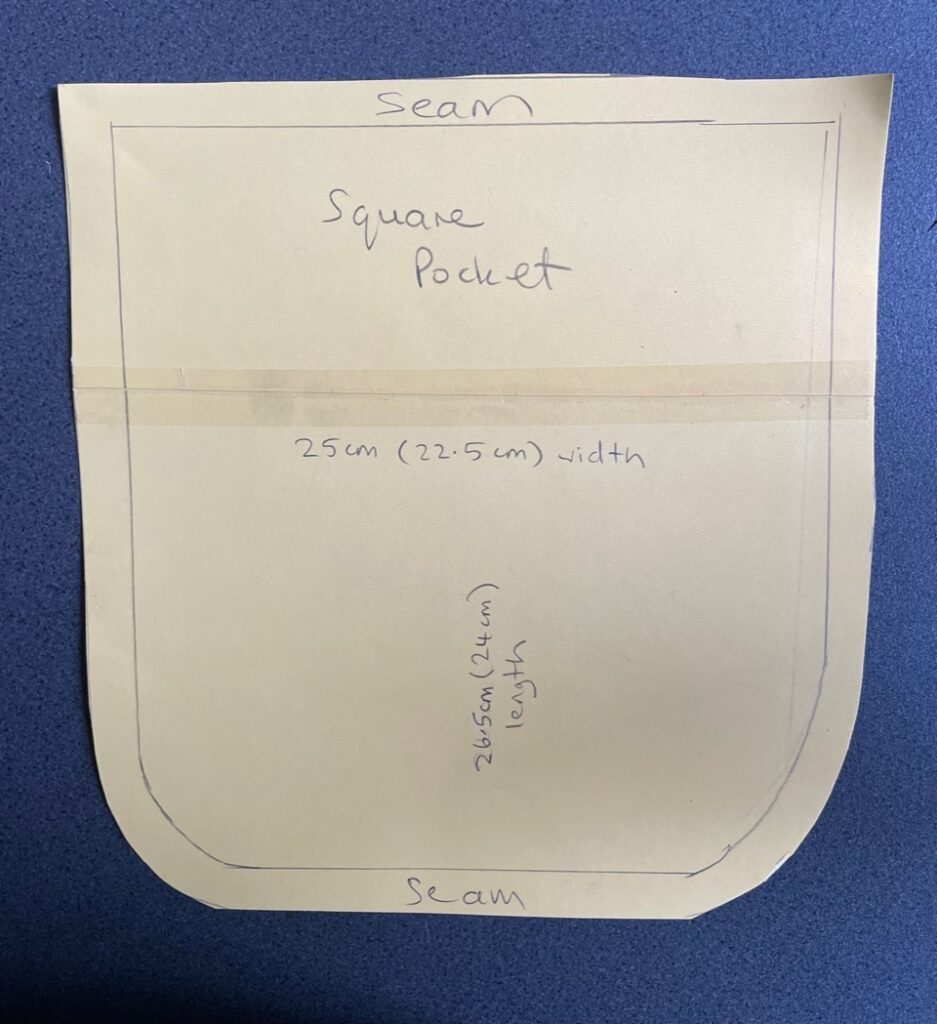

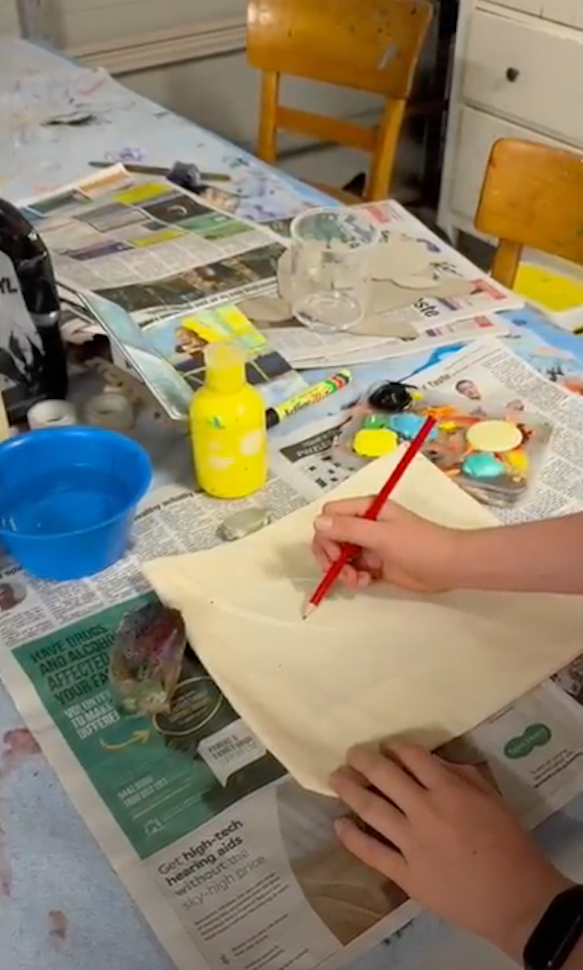

Slide 44: Step by step – pocket must face upwards with the opening at the top. Keep cardboard lining inside so that paint doesn’t seep through. Students decide on their subject matter and draw this in pencil. Write In My Pocket on the pocket. Students ask the teacher if their pocket is ready for outlining. Suggestions can be made as to what to add. Then outline in black marker. Painting process using paint, different size brushes, sponges and glitter paint. Final product hung up to dry or dry flat. Display.

Slides 45 – 49: Class groups showing their finished pockets, some students wearing their name tags.

Create Your Own Pocket

Explain to students that they will be decorating their own calico pockets, using pencils, markers and acrylic paint. Show an empty pocket.

Discuss some of the ideas and themes that came up during the brainstorm session of what the pocket could represent and/or symbolise. These could be the subject matter of their drawings and may be abstract interpretations.

The students may refer to their own personal connection to the events of the story or something suggested about behaviour and attitudes.

Students may choose to decorate their pockets with anything to do with the story, such as something already featured on a page which they would like to copy. Or they can draw their own version of it.

There are slides on the PowerPoint which have pictures that students may wish to copy or reference, such as modes of transport during the 1930s and the map of Dorrith’s journey.

The students may refer to their own personal connection to the events of the story or something suggested about behaviour and attitudes.

The students may choose to paint a sentimental item that they would keep safe in their own pocket.

The students may wish to paint something more abstract such as an emotion.

All pockets must have In My Pocket written on them and must be decorated on the front and time permitting, also on the back. The back can be multicoloured patterns made by sponging.

At each place setting: a copy of the mini book In My Pocket, the art equipment and a calico pocket.

Identity cards (like Dorrith and the other Kindertransport children wore around their necks) are distributed while pockets are drying. The student fills in the label with their own personal details and a number of their choice.

If time permits or students finish quickly, they can draw pictures of their families. Identify each family member.

Art equipment required:

For the calico pockets: cardboard or folded newspaper or thick paper inserts in each pocket to prevent paint leakage; lead pencils and erasers; black markers and some coloured markers; a selection of acrylic paints (also called poster paints) for painting on calico; paint brushes of all sizes suitable for small areas using acrylic paint; bowls of water and small sponges; a piece of plastic such as a lid or plate or a palette for the blobs of paint; extra lids for mixing colours.

For the Identity Cards with or without Reflection on the back side: craft paper cut into label shapes and plain paper with identity titles stuck onto them; string or twine threaded though a hole in the top of the label. Template available.

Extra craft paper for drawing families, time permitting.

Photos, Templates and Videos available:

- how much calico fabric is required to make the number of pockets, one per student.

- how to cut and sew the pockets.

- the step-by-step guide to decorating the pockets – drawing, painting, sponging and drying.

- the Identity Card with Reflection on the back for each student to complete while their pockets are drying.

- the Certificate of Participation (this is at the teacher’s discretion).

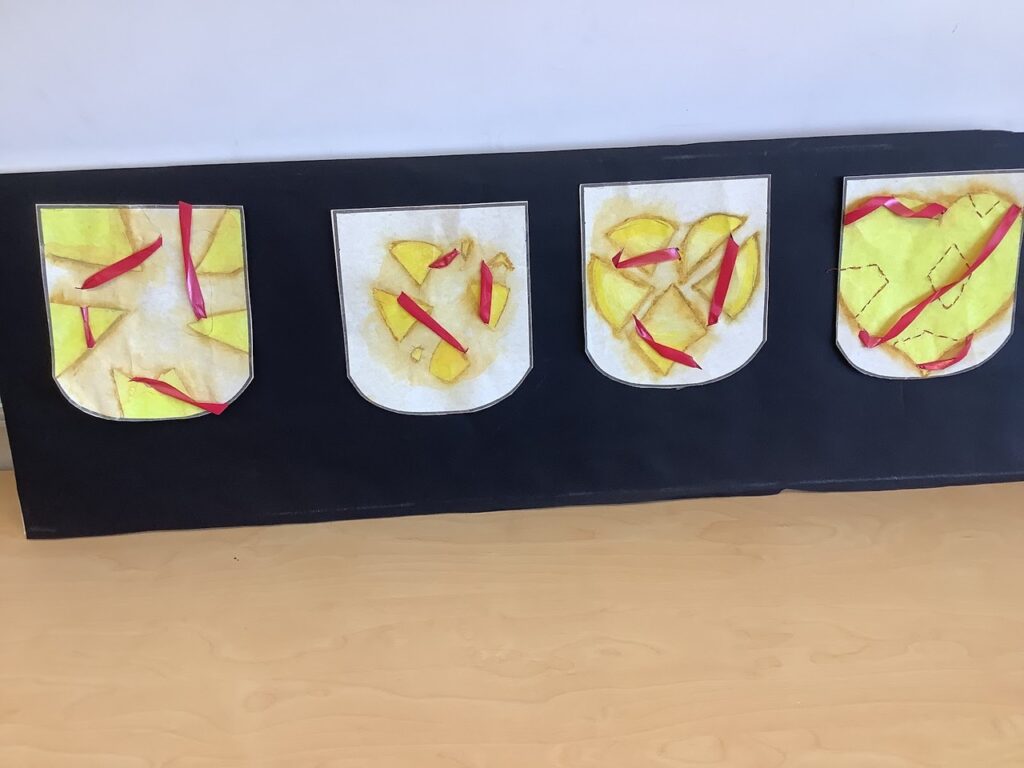

Motif – Red Ribbon

T: A motif is an image or object that is repeated in a story which helps to establish ideas. It is a recurring symbol which can reinforce the theme/s. You have seen how the red ribbon in Dorrith’s hair has been visible in almost every illustration of her. What do you think it represents? See below for some answers. Thanks to Masada College, Sydney, Year 6 students.

In My Pocket. Across all four pockets we have used the theme of love and have thought about how hard it would have been for Dorrith to leave her family and live with a new family in a new country. We have used a broken heart to show the shattered emotions of a child leaving her parents behind. A red ribbon is threaded through the heart to represent Dorrith’s connection to her family and it is this memory of love which holds Dorrith’s broken heart together. We used the colour yellow for the heart to represent hope for her new life with her new family.

In My Pocket. The red ribbon goes through the shards and around the pocket to show that it is pulling all the shards together. In my pocket the shards don’t look like a heart yet because when she gets on the kindertransport, her heart is broken because she must leave her family and live somewhere else. We used the ribbon because it is a recurring motif in the book. On every page Dorrith has a ribbon in her hair.

In My Pocket. We continued the theme of love, family and friendship. You can see how slowly throughout the book Dorrith’s heart begins to mend. We put a shattered heart in this pocket to show how Dorrith is feeling very sad and scared but she slowly learns to live with it. We had a yellow heart because the colour yellow represents hope and optimism. We used the red ribbon to mend the heart because the red ribbon is a recurring motif that we can see throughout the book. The red ribbon represents Dorrith’s past and future. In this pocket you see the love that is slowly entering Dorrith’s heart.

In My Pocket. We continued the theme of love throughout all four pockets. The motif is the red ribbon The red ribbon shows Dorrith’s connection with her past, present and future. We coloured the heart yellow because the colour yellow is present throughout all four pockets and symbolises hope and optimism. The red ribbon’s role is fixing the heart throughout all the pockets. We almost fixed the heart as Dorrith was getting closer and closer to a loving family and making friends. In my pocket you see that little Dorrith has learned to trust and be hopeful about the future.

In My Pocket. We continued the theme of love. You can see how in the end of the story Dorrith found love, a happy family and friendship. We drew a yellow full heart because yellow shows optimism and hope. We stitched some patches in the heart because even at the end of the book the cracks are still there, she still misses her family except she has learnt to live with it. Then we wrapped around a red ribbon. The red ribbon is a recurring motif that is shown in the book. The red ribbon represents Dorrith and connects her to the past and future. In my pocket you see after all that happened to little Dorrith she has learned to find happiness and love but has not forgotten her family.

By Maya, Agam, Larry, Elad

Conclusion and Evaluation of Art Component

T: Guide the students to share their pockets. * What have you created and why did you choose that image? * What special meaning will the pockets have for you when you go home?

* Art is used as a medium for consolidating the story and its impact on the students. An aspect of the story will resonate and inspire each participant to create his or her own illustration.

©2024-5 JILL RABINOWITZ All Rights Reserved

POINTS OF ARRIVAL VIDEO

POWERPOINT FOR STUDENTS

Plus short comment from Dorrith

Cross Curricular Links to Themes

1 / 19

MAKING THE POCKET VIDEO

Pocket Template

SEWING THE POCKET

PAINTING THE POCKET

POCKETS

ART EQUIPMENT

https://www.youtube.com/embed/jSGDDA0Z1Ag?feature=oembedShort Video – Boola Bardip

ID CARD & TEMPLATE

CERTIFICATE TEMPLATE